Russians and their dachas

English > Context > Social > Russians and their dachas

A dacha is a summer house on the Russian countryside. The first dachas in Russia began to appear during the reign of Peter the Great (1672-1725) after he had built Saint-Petersburg. Initially it were small estates in the country, which were given to loyal vassals by the czar. The word «dacha» comes from the verb дать [dat] or to give. By doing this, the czar held on to his staff and at the same time he could expand his new city.

In the 18th century, the aristocrats in their dachas got more neighbours from the bourgeois class and later even from middle class. At the end of the nineteenth century, dachas became common property.

Until far in the twentieth century, the dacha was a much desired, but also uneasy property. Because living on a dacha was associated by the authorities with idleness and it was considered as an unproductive use of land. According to the communist ideology, spare time should serve the construction of the socialist society and the personal development of a good citizen. But, as it happened so often, law-abiding functionaries, militaries and writers could enjoy the pleasure. The house which, in The Master and Margarita, was the ptototype of the hospital of doctor Stravinsky was the luxury dacha of the rich businessman and benefactor Sergey Pavolvich Patrikeev (1867-1914).

In the sixties and the seventies, collective dacha-parks were developed, with collective facilities. With this magic word in the name, the inspectors of the state and the party got an excuse feign ignorance of the construction of dachas. Because it was a collective organisation, no one could have ideological objections.

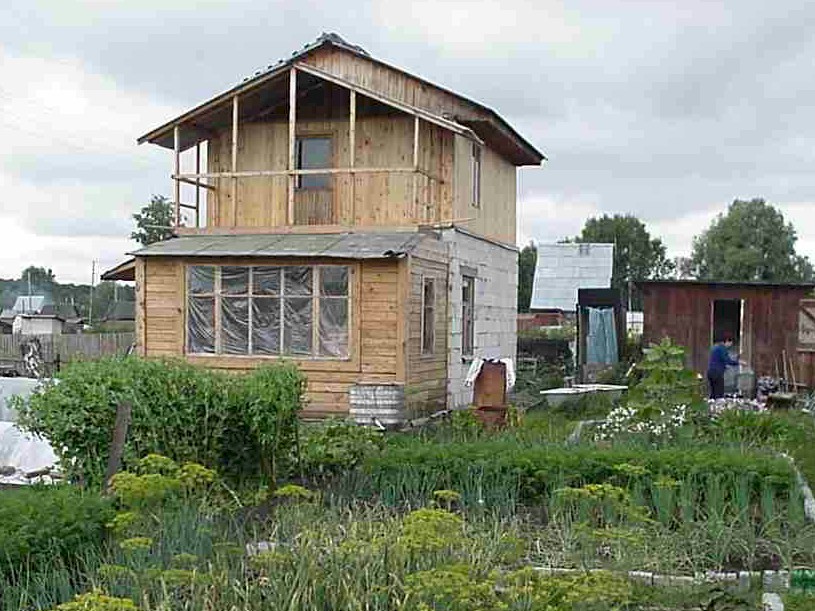

At the end of the eigthies and the beginning of the nineties many workers got a piece of land on loan from the organisation they worked for. It was a deliberate political decision: to face the food shortage in the big cities, the citizens had to grow their food themselves. On pieces of land of 600 square metres (later extended to 1200) they grew on a broad scale potatoes and vegetables suitable to build up winter stocks. On these pieces of land came soon little wooden houses.

The possession of a dacha required much ingenuity and improvisation talent. From the outside, a dacha could seem rather ordinary, but at the inside they were sometimes like little palaces. It could also be a crumbling little shed, sometimes made of old doors. Construction material was always scarce and it was often difficult to get it on the spot. You needed very good contacts for it.

At the beginning of the nineties, the possession of dachas was liberalized and became really popular. Due to the depopulation of the countryside many farmers' houses became available for the ordinary Russians. As long as there passed a train nearby, any little house was suitable to become a dacha.

Due to the privatization, millions of workers obtained dachas which until then belonged to ministries, party organs and unions. Many former state dachas were bought by a new class of citizens, the new rich.

That's what happened, for instance, to the dacha village Peredelkino, a place at 25 km south-west of Moscow where, in the Soviet time, the writers of the Writers' Union could use their dachas, and which in The Master and Margarita was described by Bulgakov as Perelygino. In 1958 it became famous when Boris Pasternak received the Nobel Prize for literature. He had a dacha there in which he wrote Doctor Zhivago. Peredelkino is now a prestigious place for a country house. Because the writers had no money to buy «their» houses, the new rich bought their wooden dachas, demolished them, and built huge palaces instead.

Bulgakov situates his Perelygino at the Klyazma river bank although the actual Peredelkino is situated at the other side of Moscow, in the southwest.

Today almost every Russian can have a dacha at his disposal. One third of all Russians spend the summer holiday on his small piece of land. When the dacha season starts in the month of May, the use of the internet drops dramatically in Russia. Because Russians love their dachas.

In the much appraised picture Утомлённые солнцем [Utomlyonnye Solntsem] by Nikita Sergeevich Michalkov (°1945) from 1994, better known by its French title Soleil Trompeur we can see colonel Kotov (Nikita Michalkov himself) with his family - his wife Maroussia, his little daughter Nadia and some grandma’s, grandpa’s, uncles and aunts) - in their dacha in 1936. They are visited by Dimitri, an old friend who once was in love with Maroussia, but who is now working for the secret police. At the end of the movie, Kotov will go with Dimitri, knowing that he will never return. With Nikita Mikhalkov as Kotov, Ingeborga Dapkunaite (°1963) as Maroussia, Nadia Michalkov (°1986), the real daughter of the director as herself, and Oleg Menchikov (°1960) as Dimitri.

The film was awarded with the Grand Prize of the Jury in Cannes (1994) and won an Oscar as Best Foreign Language Film (1995).

Share this page |