There Were Doings At Griboedov's

In A scary Saturday night. Rough sketches for the novel. 1929-1931, one of the earlier versions of The Master and Margarita, the chapter It Happened in Griboedov begins with the following sentence:

«On the evening of that scary Saturday, June 14, 1943, when the extinguished sun set behind Sadovaya, and on the Patriarch's Ponds the blood of the unfortunate Anton Antonovich [*] was mixed with meager butter on the pebbles, the writers 'restaurant Griboedov's hut was full».

Later Bulgakov rewrote this sentence as follows:

«On the evening of that scary Saturday, June 14, 1935, when the scorching sun was setting behind the bend of the Moskva River and the blood of the hapless Anton Antonovich was mixed with vegetable oil on the sidewalk, the writer's restaurant Griboedov's hut was full».

Nowhere else in the novel Bulgakov gave an exact date for the events. Why he did it here remains a mystery to me. Especially because something is not right.

According to Russian philologist Victor Ivanovitch Losev (°1939), there woulfd be the following entry in one of Bulgakov's notebooks: «Mikhail Nostradamus, born 1503. End of the world 1943». Michel de Nostredame (1503-1566), better known as Nostradamus, was a French pharmacist and astrologer best known for Les Prophéties, a work of 942 predictive quatrains or four-line verses, the first edition of which was published in 1555.

Bulgakov had read Nostradamus' name in the Энциклопедический словарь Брокгауза и Ефрона [Entsiklopedesky slovar Brokhauza i Efrona] or the Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary, a work of 86 volumes which can be regarded as an equivalent of the Encyclopaedia Brittanica.

Under the entry Nostradamus we can read in that dictionary that «the end of the world would take place in the year in which Good Friday coibcides with the feast day of Saint George (23 April), Easter with the feast day of Saint Mark (25 April) and Corpus Christi with the feast day of John the Baptist (24 June)». This concurrence had happened before, in 1886, and would take place a next time in 1943.

Why Bulgakov chose the year 1943 in A scary Saturday night can therefore be explained. Why he changed it afterwards in 1935 is less clear. And why he twice described a Saturday, June 14, I don't know either. In the year 1930, when Bulgakov was writing this version of the novel, June 14 was indeed a Saturday, but June 14, 1943 was on a Monday, and June 14, 1935 was on a Friday.

[*] In this version of the novel, Berlioz was not called Mikhail Alexandrovich Berlioz, but Anton Antonovich Berlioz.

Alexander Sergeevich Griboedov

The poet, playwright and diplomat Alexander Sergeevich Griboedov (1795-1829) is best known as the author of the comedy Горе от ума [Gorye ot uma] or Woe from Wit, the first real masterpiece of the Russian theatre.

Alexander Sergeevich Griboedov

But the Griboedov house never really existed. When following Bulgakov's routemap, we arrive at Tverskoy Boulevard 25. There's a house that fits the description: the Herzen house, where Alexander Ivanovich Herzen (1812-1870), another Russian author, was born in 1812.

The Herzen house

The role of the original Herzen house corresponds to Gribodeov in the book. The Herzen house was the home of many literary organizations in the twenties. The Российская Ассоциация Пролетарских Писателей (РАПП) [Rossiyskaya Assotsiatsiya Proletarskikh Pisateley (RAPP)] or Russian Association of Proletarian Writers, the Московская Ассоциация Пролетарских Писателей (MAPP) [Moskovskaya Assotsiatsiya Proletarskikh Pisateley (MAPP)] or Moscow Association of Proletarian Writers and the Литературный Организация Красной Армии и Флота (ЛОКАФ) [Literaturniy Organizatsiya Krasnoy Armiy i Flota (LOKAF)] or the Literary Union of the Red Army and the Marine. The names of these organisations are real: much hideous abbreviations were commonly used in the Soviet Union. Bulgakov based the fictive MASSOLIT on the RAPP and the MAPP.

The RAPP with Leopold Averbach in the middle

In The Master and Margarita, Bulgakov gives no explanation for the abbrevation MASSOLIT. But it probably was the Мастера Социалистической литературы [Mastera Sotsialisticheskoy literatury] or Masters for Socialist Literature, by analogy with the Мастера Коммунистической Драмы (МАСТКОМДРАМ) [Mastera Kommunisticheskoy Dramy (MASTKOMDRAM)] or Masters for Communist Drama, an organisation that really existed in Bulgakov's era.

Until 1931 there was a writers' restaurant in the Herzen house. Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky (1894-1930) criticized it heavily in his satirical poem Herzen house. Since 1930 it is the home of the Maxim Gorki Literary Institute, where aspirant-writers are trained.

A seedy garden

Bulgakov uses the term чахлый сад [chakhli sad] or stunted garden. Michael Glenny translated it as a «ragged garden». These days, the front yard of the Herzen house can’t certainly not be described as «seedy», «ragged» or «stunted». I do not know how the garden looked like in the time of Bulgakov, but it seems that, with this description, he wanted to start polemics with Vladimir Mayakovsky (1893-1930), in particular because of the optimistic pathos which the latter showed in his famous verses from the poem Khrenov’s Story of Kuznetsktroy and the People of Kuznetsk.

«I know - the city will come

I know - the garden will bloom

When there exist such people

In the Soviet country»

This poem from 1929 heralded the construction of the Siberian industrial city of Novokuznetsk, which was then called Kuznetsk. The Stalinist industrialization would transform Kuznetsk in the 1930s into a major center of coal mining and industry, and used the urbanization principles of the Garden City. The Garden City was a method of urban planning, developed in 1898 by the English Sir Ebenezer Howard (1850-1928). Garden Cities were planned, self-sufficient communities, surrounded by green belts, with proportional zones for housing, industry and agriculture. Bulgakov was quite skeptical to this principle, especially with relation to the proportionality, and he reproached Mayakovsky that he had written an ode to a city he had never visited himself.

Eventually, Bulgakov would be right in being skeptical. Despite the green belt, Novokuznetsk now has one of the highest concentrations of air pollution in Russia. According to a survey from 1997, the sulfur concentration at one of the factories was 312 times the allowable standard, the fluoride concentration at a pharmaceutical factory 300 times, and the benzopyrene of the city 10 times.

The video below about Novokuznetsk was made in 1949 to glorify 20 years of Stalin City. After 39 seconds, you hear the above mentioned verses of Mayakovsky.

The verse of Mayakovsky was again very popular in 2014 among critics of the regime of Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin (°1952). It was eagerly resumed on blogs and social media when it appeared that, barely six weeks after the Winter Olympic Games in Sochi, virtually the entire infrastructure that was built for it was turned into a ghost town. The organisation of these games had cost 51 billion dollar.

M. V. Spurioznaya

In the original Russian text the person to whom should be applied for One-Day Creative Trips is not called M. V. Spurioznaya, but М. В. Подложная [M.V. Podlozhnaya]. This name is not without a meaning: the Russian word подложный [podlozhny] means false, untrue, faked.

Perelygino

The name Perelygino is clearly meant to suggest the actual Peredelkino, a writers' village near Moscow where many writers were allotted country houses. It was a privileged and highly desirable place.

The name Perelygino is not just a simple transformation of Peredelkino, because the Russian word лгун [lgun] means liar. In one of the earlier versions of the novel this writers' village was called Перевракино [Perevrakino], which comes from враки [vraki] or lies. What it boils down to is that Perelygino means as much as Liars' Village.

In 1958, Peredelkino became very famous when Boris Leonidovich Pasternak (1890-1960) won the Nobel Prize for Literature. He had a dacha there and worked there on his novel Doctor Zhivago. Nowadays the new rich are buying the whole village. They demolish the wooden houses for replacing them by luxury palaces.

Boris Pasternak's dacha at Peredelkino

Yalta, Suuk-Su... (Winter Palace)

To this list of resort towns in the Crimea, the Caucasus and Kazakhstan, Bulgakov incongruously adds the Winter Palace in Leningrad, which was the former residence of the emperors.

And what a restaurant!

Until the last days of the Soviet Union, restaurants belonging to the Writers' Union, the Journalists' Union, the Union of Cinematographers, and the Actors' Union were among the best and cheapest in Moscow, but to get in, one needed an ID from these organisations.

Amvrosy and Foka

Amvrosy comes from the Greek word αμβροσία [ambrosia], or immortal and it was also the name of the food of the gods conferring immortality on whoever consumed it. Foka is the name of the hero of the fable Demyan's Fish Soup by the most famous Russian fabulist Ivan Andreevich Krylov (1769-1844). Foka rejects excess, notably of foods.

The Coliseum, where you can get slapped in the mug with a bunch of grapes by a young man

Some Bulgakov scholars think that the Колизей [Kolizej] or Coliseum is the restaurant of hotel Metropol in Moscow. But it is more likely that Bulgakov was thinking of the Дом Союзов [Dom Soyuzov] or House of the Unions, and more in particular its Колонный зал [Kolonniy zal] or Colonnade. Because Колизей [Kolizej] could be a contraction of Колонный зал [Kolonniy zal].

On August 17, 1934 the First Congress of the newly created Союз советских писателей [Soyuz Sovyetskikh Pisateley] or Soviet Writers' Union was organised in this hall. Bulgakov was not invited for this event, but he had heard how things went there. The delegates were spoiled rather generously. Per person and per day, the organisation spent 40 roubles on food. For comparison: an ordinary dinner was about 85 kopecks in those days, and in a fancy restaurant you could pay up to 5 roubles for it. The incident with the bunch of grapes refers to the final banquet of the Congres in the Colonnade. Many people were drunk and a young poet had struck Alexander Yakovlevich Tairov (1885-1950), the director of the Камерный театр [Kamerny teater] or Chamber Theatre. In 1928-1929, Tairov had played more than 60 times Bulgakov's theatre play The Crimson Island.

The Colonnade of the House of the Unions

In it languished twelve writers

«In it languished twelve writers who had gathered for a meeting and were waiting for Mikhail Alexandrovich». This sentence is a typical example of the satirical device to swap situations from one world to another. The writers in Griboedov seem to be the apostles waiting for Jesus at the Last Supper.

Rather than parodying specific writers, Bulgakov employs Gogol's device of significant and funny-sounding names in this passage. Глухарев [Glukharev] means black grouse, Драгунский [Dragunsky] means dragoon, Павианов [Pavyanov] - translated as Baboonov in the English text - means baboon, and Богохульский [Borokhulsky] - translated as Blasphemsky - means blasphemer.

The belletrist Beskudnikov

The belletrist Beskudnikov is a «quiet, decently dressed man with attentive and at the same time elusive eyes». In an earlier version of the novel he was depicted as «a good looking, Frenchy man with a suit and solid shoes made in France». The real life prototype for the belletrist Beskudnikov could have been the writer and playwright Vladimir Mikhailovich Kirshon (1902-1938), one of the secretaries of the RAPP in Moscow, and one of the most relentless persecutors of Bulgakov. In August 1937, Kirshon was arrested along with other former RAPP leaders, and the next year he was executed at the Butyrka prison in Moscow.

But in the third version of The Master and Margarita, on which Bulgakov worked from 1932 to 1934, the Beskudnikov character was introduced as «the chairmain of the Playwrights Section» of MASSOLIT. This could be an indication that its real life prototype was Yuri Livovich Slyozkin (1885-1947). In his notebooks, under the title Results 1928-1929, Bulgakov wrote: «Slyozkin proudly announced his appointment as the Chairman of the Bureau of the Drama Section». Slyozkin was a novelist which Bulgakov had met in 1920 in Vladikavkaz. One year later, he had introduced Bulgakov in the literary circles of Moscow. But in 1925, this «supposed friend» would use him in a rather malicious manner as a prototype for the journalist Alexey Vasilievich in his novel Девушка с гор [Debushka s gor] or The girl from the mountains. In return, Bulgakov would use Slyozkin as a prototype for the elderly, patronizing and jealous writer Likospastov - «an unbelievable scum» - in his Theatrical Novel.

The poet Dvubratsky

Dvubratsky is derived from the Russian word Двубратский [dvubratsky], which means two-brotherly, but which is also used to say opportunistic. It is likely that the poet and translator Alexander Ilich Bezymensky (1898-1973) was the real prototype for Dvubratsky. Bezymensky means The Nameless, which feeds the theory of some scholars that Bezymensky could as well have been the real prototype of Ivan Bezdomny, the Homeless. The name Bezymensky was not a pseudonym, though. But Bezymensky was such a proletarian poet that he said: «if Bezymensky had not been my birth name, I would have taken it as a pseudonym».

In 1929, Bezymensky had written a theatre play Выстрел [Vystrel] or The Shot, which partly was a parody of Bulgakov's The Days of the Turbins. In the 1929-1932 version of The Master and Margarita, the poet Dvubratsky was called Aleksandr Ivanovich Zhitomirsky. Zhitomir is the city, 140 km west from Kiev, where Bezymensky was born.

Alexander Ilich Bezymensky

Boz'n George

Behind Boz'n George, the male pseudonym for the female writer Natasha Lukinisha Nepremenova in the novel, we suppose a parody of the French writer Amandine Dupin (1804-1876) who used the pseudonym Georges Sand. Sand was a 19th-century feminist, who had a relation of nine years with the composer Frédéric Chopin (1810-1849). She wrote novels inspired by socialism and was politically active as a member of the Temporary Government in 1848, in the build-up to the Second Republic in France.

Georges Sand (Amandine Dupin)

However, according to Elena Sergeevna, Bulgakov's third wife, he would have integrated some more writers in his description of the Boz'n George character. Like, for instance, the playwright Sofya Aleksandrovna Apraksina-Lavrinaitis (1885-?), who used the male pseudonym Сергей Мятежный [Sergey Myatezhny] or Sergey the Rebel. She knew Bulgakov and presented him, in 1939, a libretto for the Bolshoy Theatre.

The scenarist Glukharev

Glukharev is derived from the Russian word глухарь [glukhar], which is a grouse, a bird of the family of the gallinaceans.

Tamara Polumesyats

The name Полумесяц [Polumesyats] means half moon.

The novelist Zhukopov

Zhukopov is derived from the Russian word жук [zhuk], which means beetle or bug. According to the Russian psychologist and translator Valery Konstantinovich Mershavka (°1957), Bulgakov would have found his inspiration for this character with Alexander Gavrilovich Shlyapnikov (1885-1937), a revolutionary of the first hour who was leader of the so-called Workers' Opposition in the 1920s. In 1931, Shlyapnikov published the book On the eve of 1917, with his memoirs about the Russian Revolution. However, we have not found any confirmation that Shlyapnikov would be the prototype of Zhukopov.

some movie actress in a yellow dress

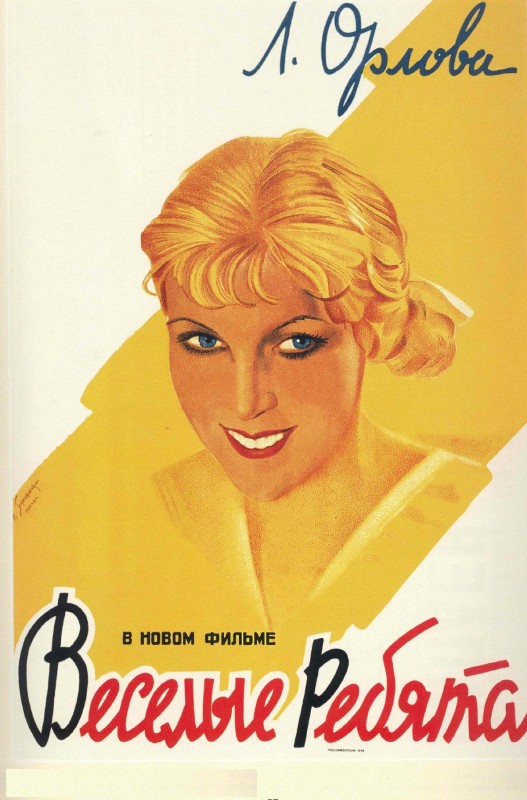

In the early versions of The Master and Margarita, Zhukopov the novelist danced just «with a movie actress». It was only in 1934 that this description was changed into «some movie actress in a yellow dress». We therefore have good reasons to believe that the prototype of this movie actress was none other than Lyubov Petrovna Orlova (1902-1975).

Indeed, in 1934, the successful film Весёлые ребята [Besyolye rebyata] or Jolly Fellows by director Grigory Vasilevich Aleksandrov (1903-1983) was released in Russia, with Orlova, the director's wife, in the leading role. The film was of course in black and white, but Orlova shone in a yellow dress on the poster, made by Yosif Vasilevich Gerasimovich (1894-1982).

Lyubov Petrovna Orlova

Two years later, the couple Aleksandrov-Orlova would make Цирк [Tsirk] or The Circus, a propagandist movie which glorified the Soviet regime, and about which you can read more in the Context section of the Master & Margarita website by clicking the arrow below.

Cherdakchi

Cherdakchi is derived from the Russian word чердак [cherdak], which means attic, junk room or loft.

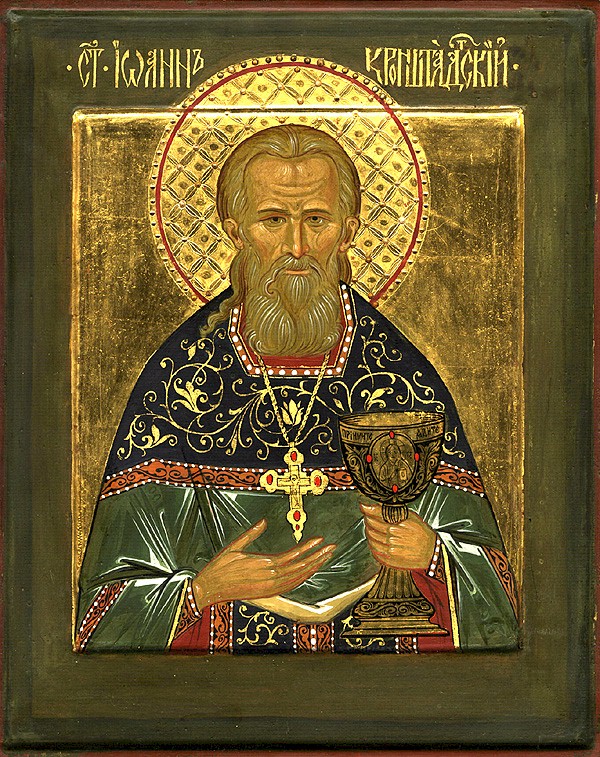

The writer Johann from Kronstadt

With this character Bulgakov refers to the two film scripts written by Vsevolod Vitalyevich Vishnevsky (1900-1951), the man who inspired him to study in depth the character of Mstislav Lavrovich. In these scripts, We from Kronstadt (1933) and We are the Russian People (1937), there is a charachter named Johann Ilyich Sergeev (1829-1908), nicknamed Father Johann, rector of the cathedral of Kronstadt, which is not far from Saint-Petersburg. He organised many activities for the poor and was canonized by the Russian orthodox church.

Johann Ilyich Sergeev (Father Johann)

Mstislav Lavrovich

Mstislav Lavrovich is a parody to Vsevolod Vitalyevich Vishnevsky (1900-1951), novellist and playwright and rabid rival of Bulgakov. He prevented that Bulgakov's pieces Бег [Beg] or The Flight and Мольер [Molière] could be performed at the Moscow Art Theatre MKhAT.

Klyazma

The Klyazma is a river in the Moscow, Nizhny Novgorod and Vladimir oblasts in Russia, a left tributary of the Oka River. The length of the river is 686 km. Bulgakov situates his Perelygino at the Klyazma river bank although the actual Peredelkino is situated at the other side of Moscow, in the southwest.

Dachas

A dacha is a summer house at the Russian countryside. The Russian custom to have a summer house originated in the first years after the construction of Saint Petersburg. The word дача [dacha] comes from the verb дать [dat'], which means to give. Czar Peter the Great (1672-1725) gave pieces of land in the countryside to highly ranked officials to build a villa. By doing so, he bound his people to himself and he could extend his new city at the same time.

Until the end of the twentieth century the dacha was a coveted, but also uncomfortable possession. Living on the dacha was associated by the authorities with doing nothing and with the unproductive use of land. According to the communist ideology free time should be spent to the advancement of the socialist society and the personal development to become a good citizen. But, like in many other situations, faithful officials, military officers and writers could enjoy it fully.

The atmosphere in a dacha during the Stalin era is extremely well depicted in the much appraised picture Утомлённые солнцем [Utomlyonnye Solntsem] or Burnt By The Sun by Nikita Sergeevich Michalkov (°1945) from 1994, better known by its French title Soleil Trompeur. We can see how colonel Kotov spends a holiday with his family - his wife Maroussia, his little daughter Nadia and some grandma’s, grandpa’s, uncles and aunts - in their dacha in 1936.

You can read more about the Russians and their dachas in the Context section of the Master & Margarita website by clicking the arrow below.

Zheldybin

I don't know (yet) if there exists a real prototype for the writer Zheldybin, Berlioz' assistant in Massolit, summoned by telephone from his sick wife's side.

Hallelujah

This charleston written by Vincent Youmans (1898-1946), and which Bulgakov loved very much, appears three times in the novel.

Here you can see how the Griboedov jazz band plays Hallelujah in the TV-series Master i Margarita made by the Russian director Vladimir Bortko in 2005.

You can read more about the charleston Hallelujah in the section Themes, style and form of the Master & Margarita website by clicking the arrow below.

The famous Griboedov jazz band

With this jazz band, Bulgakov was referring to the ensemble Московские ребята [Moskovskiye rebyata] or Moscow Friends, also known as the Aleksandr Tsfasman Jazz Band. Aleksandr Tsfasman (1906-1971) played a major role in the development of popular music in the Soviet Union since the mid-20s. In 1923, he became head of the music department of the Griboedov Drama Studio in Moscow.

In 1926, Tsfasman with his band recorded the very first jazz album in the Soviet Union with the song Hallelujah, mentioned in the previous paragraph, and he also played regularly at the restaurant Casino at the Triumfalnaya Square, at only a few steps from Bolshaya Sadovaya ulitsa no. 10.

One Karsky shashlik

«One Karsky shashlik! Two Zubrovkas! Home-style tripe!», a voice commands through a megaphone while the jazz band plays «Halleluja». At first, I had not planned to write an annotation about this order, until I noticed that different dishes are ordered in the Dutch, English and French translations of The Master and Margarita - and that they don't correspond to Bulgakov’s text. Have a look:

«Karbonade eenmaal! Sjasliek tweemaal! Van de haas driemaal!» (Fondse/Prins - Dutch)

«Chops once! Kebab twice! Chicken a la King!»(Glenny - English)

«One Karsky shashlik! Two Zubrovkas! Home-style tripe!» (Pevear - English)

«Une brochette à la kars, une ! Deux vodka Zoubrovka, deux ! En flacons de maîtres!» (Ligny - French)

In the Russian source text we can read: «Карский раз! Зубрик два! Фляки господарские», which should be translated as:

«One Karsky shashlik! Two Zubrovkas! One Fliyaki gospodarskye!»

I admit, it's not easy. But today the internet offers the possibility to find out what it's all about. Karsky shashlik is a Karsky meat spit - prepared like they do at the Kara Sea (which is a part of the Arctic Ocean). It's an unusual dish, because in the northern part of Siberia one expects fish dishes rather than meat.

Zubrovka is a Polish vodka with a tincture (alcoholic solution) of Hierochloe odorata, also called sweetgrass or bison grass. That's why it may not be imported into the United States, since sweetgrass contains, like many other gramineous or meadow plants, coumarin. This substance has a sweet scent, readily recognised as the scent of newly-mown hay, but it's also carcinogenic.

No wonder that the translators didn't know how to deal with Fliyaki gospodarskye. Because the Russians hardly know it either. On dozens of websites is asked «что же такое «фляки господарские» и с чем их едят?» or «what is Fliyaki gospodarskye for heaven's sake and how do you eat it?» The English «home-style tripe» translation by Pevear is closest to the truth. The authors of the website www.cooking.ru found the answer after a long search effort. It's a soup of intestines. To prepare it, you need: 1kg of intestines of beef, 400 grams of vegetables, 500 grams of bones of beef, 60 grams of lard, 30 grams of flower, nutmeg, red and black pepper, ginger, oregano, salt, and 50 grams of Swiss cheese. Приятного аппетита! [Priatnevo appetita!] or Bon appétit!

A handsome dark-eyed man with a dagger-like beard

The prototype for Archibald Archibaldovich was Yakov Danilovich Rozental (1893-1966), nicknamed the Beard. Therefore Bulgakov called him the Pirate.

Yakov Rozental was the manager of the restaurant of the Hertzen House, which was the prototype for the Griboedov House, and the restaurant of the Journalists' Union from 1925 to 1931. The Bulgakovs were acquainted with Rozental, and Elena Sergeevna mentioned him in her diary.

Yakov Danilovich Rozental

Oh, gods, my gods, poison, bring me poison!

The narrator quotes once more the words of Verdi's Aïda which Pilatus already used in chapter 2 of the novel.

Let's not burden the telegraph wires any more

The novel is interlarded with references to works of other Russian writers. With this expression Bulgakov quotes the Russian poet Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky (1893-1930), with whom he often played billiard, but who would, in 1928, join the ones who summoned to ban The Days of the Turbins. Mayakovsky committed suicide in 1930. Here's an excerpt from the unfinished poem Bulgakov refers to:

«...there's no need

to burden you with the lightning of my cables.»

But, as for us, we're alive!

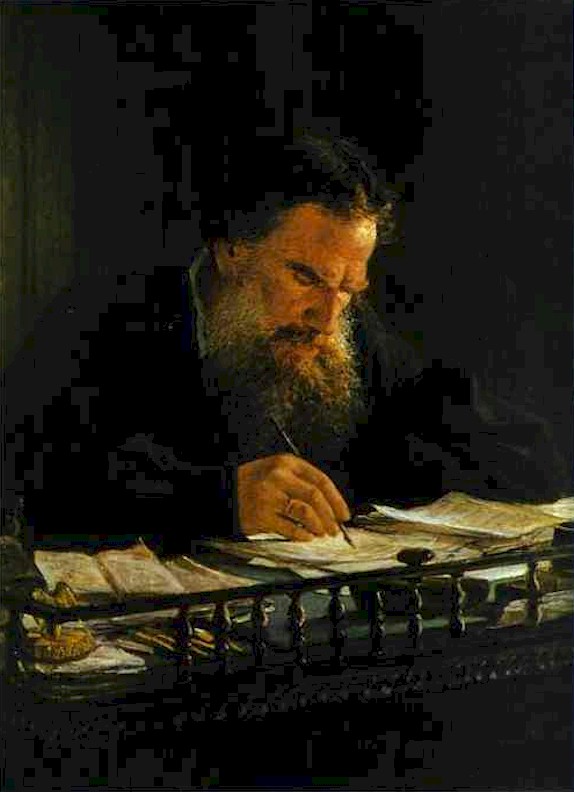

«Yes, he's dead, dead... But, as for us, we're alive!» Here Bulgakov quotes from the novella The Death of Ivan Ilyich by Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy (1828-1910). It's from Tolstoy’s late period and it is considered as one of his best works. The characters of this story had exactly the same reaction when Ivan Ilyich died: everyone who heard of it said: «Well, he's dead, but, as for me, I'm alive!»

Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy

What last name begins with «W»?

«We, Wi, Wa, Wu... Wagner?» is another reference to another literary work. This time to Goethe’s Faust. Wagner is the research assistant of doctor Faust.

Coachman

Though increasingly replaced by automobiles, horse-drawn cabs were still in use in Moscow until around 1940.

Riukhin

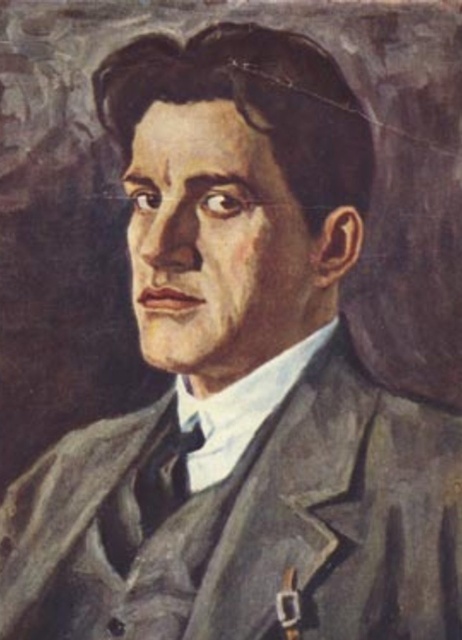

Through the conversation with Pushkin's statue, Bulgakov makes clear who is the prototype for Riukhin. It's Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky (1893-1930) who, in 1924, at the occasion of the celebration of the 125th anniversary of Pushkin's birth, wrote the poem Jubilee in which, at night, he lifts up Pushkin from his plinth at Tverskaya bulvar and introduces him into his thoughts on a walk through the streets of Moscow.

Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky

The quarrel between Riukhin and Ivan Bezdomny in the novel is a parody of the always changing relation between Mayakovsky and another poet, Alexander Ilich Bezymensky (1898-1973), who was mentioned earlier on this pages as The Nameless.