Schizophrenia, As We Said

Greetings, saboteur!

Ivan uses standard terms from Soviet mass campaigns against so-called enemies of the people. Anyone thought to be working against the aims of the ruling party could be denounced and arrested as a saboteur.

Actually, Ivan says «Здорово, вредитель» [Zodorovo, vreditel], which means «Hi, vermin». But the translation is correct in its meaning, because the Soviets had countless synonyms to define so-called saboteurs, and вредитель [vreditel] or vermin is one of them. It was mainly used to indicate someone who worked against the regime from inside by sabotaging the machines or by messing up the production planning.

That giftless goof Sashka

This reproach from Ivan Bezdomny to Riukhin is based on the animosity between their prototypes, the poets Alexander Illich Bezymensky (1898-1973) and Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky (1893-1930), who didn’t get along. At first, Mayakovsky was Bezymensky's idol, but the feeling was not reciprocated. Mayakovsky compared Bezymensky's work to «coffee made of carrots». With «carrots» he means chicory, so he compares him to substitute coffee.

A typical little kulak

Кулак [kulak] is actually Russian for fist, but it's also the name given to rich or successful peasants in the Soviet Union. Stalin ordered their liquidation in 1930.

After the abolishment of the serfdom in 1861 a minority of farmers in the Russian Empire succeeded to develop to a prosperous and independent peasant class. The power and influence of these kulaks in the villages was dashed by the communists. The medium-sized farmers, the serednyaki, were forced to join kolkhozy or collective state farms.

Those resounding verses he wrote for the First of May

In the Russian text Bulgakov didn’t say that Riukhin's verses were about the First of May. He wrote: «Сличите с теми звучными стихами, который он сочинил к первому числу!» or «Compare it to those resounding verses he wrote for the first!» So Bulgakov didn't specify which «first», which made the English translators Diana Burgin and Katherine Tiernan O'Connor think that Riukhin’s verses were about New Year.

But it were indeed verses for the First of May, and more in particular May 1, 1924. Bezdomny is referring to the poem Jubilee, written by Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky (1893-1930) for the celebration of the 125th anniversary of the birthday of Aleksandr Sergeevich Pushkin (1799-1837). This poem was quite resounding, as you can judge yourself here:

«Александр Сергеевич, разрешите представиться. Маяковский.»

«Aleksandr Sergeevich, let me introduce myself. Mayakovsky.»

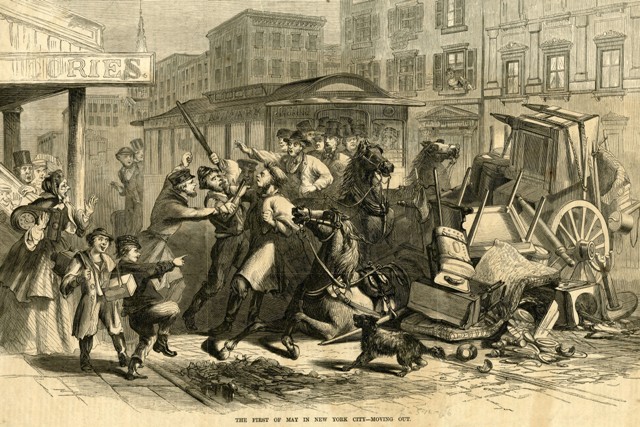

May 1 is the International Labour Day. The date of May 1 wasn’t chosen by coincidence. In the United States, May 1 was called Moving Day. On that day all existing labour contracts and all existing housing contracts were to be renewed. On the May 1 celebration in 1886 there were heavy fights in Chicago. Three years later, on July 21, 1889, at the first congress of the Second International in Paris, the socialist movement in Europe decided to celebrate May 1 as Labour Day. The aim was to support the growing demands for an 8 hours working day. On May 1, 1890, the first celebrations were organized in many countries.

Moving Day in New York

«Soaring up!» and «Soaring down!!»

In this passage, Bezdomny clearly wants to denounce the bombastic propaganda style used by Riukhin in his poems. To illustrate that, «Soaring up and soaring down!» sounds okay, but is a very «free» translation of what Bulgakov really wrote. In the original Russian text of the novel we read: «Взвейтесь! да развейтесь!», which means «Stand up! Yes, disperse!». Those words refer to Взвейтесь кострами [Vsveytes kostrami] or Set up the bonfires, the first Pioneer song written in the Soviet Union.

At a meeting of the Central Committee of the Komsomol in May 1922, Nadezhda Konstantinovna Krupskaya (1869-1939), the wife of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin (1870-1924), suggested the idea of creating Pioneer songs. The poet Aleksandr Alekseevich Zharov (1904-1984) was requested to write a song - a march - within two weeks. In his memoirs, Zharov wrote that, because of the time pressure, the writer Dmitry Andreevich Furmanov (1891-1926) advised him to start from something existing. When the company went to the Moscow Bolshoy Theatre to watch the opera Faust by Charles Gounod (1818-1893), Zharov took the March of the Soldiers from this opera as a basis to write his lyrics. Sergey Fodorovich Kaydan-Dyoshkin (1901-1972), a music college student, «adapted Gounod's march to the Pioneers' clarions», and «the first Pioneer song was born».

You can listen to Set up the bonfires here:

A corridor, lit by blue night-lights

Again, we see a reference to Freemasonry. Before the Apprentice initiation ritual, the candidate is ushered in the «chamber of reflection», a small darkened room adjoining the Lodge room, usually in the basement of the temple building.

The interest of Bulgakov for Freemasonry can be explained by the fact that, in 1903, Afanasy Ivanovich Bulgakov (1859-1907), theologian and church historian, and the father of Mikhail Afanasievich, had written an article about Modern Freemasonry in its Relationship with the Church and the State, which was published in the Acts of the Theological Academy of Kiev. Bulgakov refers more than once to Freemasonry in the novel.

You can read more on Freemasonry in The Master and Margarita in the Context section of the «Master & Margarita» website by clicking the arrow below.

A metal man

The «metal man, his head inclined slightly, gazing at the boulevard with indifference» is a description of the big statue of Aleksandr Sergeevich Pushkin (1799-1837) in Moscow. The «big statue», because there are several other statues of Pushkin in Moscow. This metal man stands on Pushkin square, looking over Tverskaya ulitsa, the busiest shopping street in Moscow.

The metal man, his head inclined slightly

You can read more on Aleksandr Sergeevich Pushkin in the Context section of the «Master & Margarita» website by clicking the arrow below.

The snowstorm covers

This is the first line of Winter Evening (1825), one of the most anthologized poems written by Aleksandr Sergeevich Pushkin (1799-1837).

A glass of Abrau wine in his hand

Abrau-Durso is a city in the Novorossiysk region in Russia where, since 1870, champagne and wines are produced. The vintages are situated at the Black sea coast.

It was prince Lev Sergeevich Golitsyne (1845-1916) who brought to Russia the recepy of champagne discovered 200 years earlier by the monk Dom Pierre Pérignon (1638-1715). He started the production of it in Abrau Durso.

On July 2, 2021, the Russian President Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin (°1952) hijacked rather shamelessly the name champagne with a strange law. Despite international patent protection, from now on, only wines produced in Russia may bear the name шампанское (shampanskoye] or champagne. Wines of foreign origin, including the genuine French champagne, may only be labeled игристое вино [gristoye vino ] or sparkling wine.

The French translator Claude Ligny seemed very far-sighted in this regard. He translated Bulgakov's words с бокалом «Абрау» в руке [s bokalom «Abrau» v rukye] or with a glass of «Abrau» in his hand as une coupe de champagne à la main or with a glass of champagne in his hand.

A bottle of Abrau Durso with sweets