Барон Майгель

Русский > Персонажи > Московские персонажи > Барон Майгель

Мы продолжаем напряженно работать, чтобы улучшить наш сайт и перевести его на другие языки. Русская версия этой страницы еще не совсем готова. Поэтому мы представляем здесь пока английскую версию. Мы благодарим вас за понимание.

Context

At Satan's ball, in chapter 23, the «dear baron Meigel, an employee of the Spectacles Commission», entered the ballroom «quite alone». In his function as a «guide for foreigners» he «acquainted people with places of interest in Moscow». As soon as the baron had heard of Woland's arrival in Moscow, he offered him «his expertise». Margarita recognized this Meigel. She had «come across him several times in Moscow theatres and restaurants».

But Woland knew Meigel's intensions. He told him that rumours have spread about the baron's «extreme curiosity». In other words: the Baron was a spy. Woland suspected that Meigel had tried to manoeuvre himself in his favour in order to eavesdrop on him. And he ordered Abaddon to kill Meigel.

Prototype

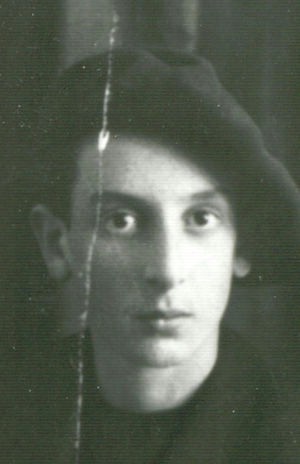

The real prototype for Baron Meigel's character is Baron Boris Sergeevich (von) Steiger (1892-1937). In the '20's and '30's, this baron worked in Moscow at the Народный комиссариат просвещения (Наркомпрос) [Narodny kommisariat prosveshcheniya] (Narkompros) or People's Commissariat for Enlightening, where he was responsible for External Relations. Simultaneously he worked as an agent of the Объединённое государственное политическое управление (ОГПУ) [Obedinyonnoe gosudarstvennoe politicheskoye upravlenye] (OGPU) or the United State Political Administration, the secret service which became part of the notorious NKVD in 1934. In 1937, Steiger was arrested and executed.

Steiger is mentioned several times in the diary of Elena Sergeevna Shilovskaya (1893-1970). He was often found at the embassy of the United States. He reported on foreigners connected with the theatre, and on Soviet citizens having contact with the embassy. Steiger was often present at the excentric receptions organised by the American ambassador William Bullitt in the years 1934-1936.

One of these parties, organised on April 23, 1935, inspired Mikhail Bulgakov for his description of Satan's Grand Ball in The Master and Margarita. After this party, Bulgakov and Elena Sergeevna were taken back home with a car of the embassy, and Baron Boris Steiger suddenly accompanied them. Elena Sergeevna wrote in her diary: «We wanted to leave the place at half past three but they did not allow us to leave. We left at half past five in one of the cars of the embassy. A certain Steiger, I believe, a man whom we do not know but whom all Moscow knows and who can always be found when there are foreigners, joined us in the car. He was sitting next to the driver and we were in the rear. It was already daylight when we arrived home».

Steiger had good connections abroad. His brother was the poet Baron Anatoly Sergeevich Steiger (1907-1944) and his sister was the poetess Baroness Alla Sergeevna Steiger-Golovina (1909-1987). Both escaped during the revolution. They lived successively in Turkey, Czechoslovakia, France and Switzerland. Sister Alla moved to Brussels in 1955. Before the revolution, their father, baron Sergey Edwardovich Steiger (1868-1937), was deputy in the Duma for the Kanev district in Ukraine.

Steiger was arrested and shot in 1937, together with Avel Sofronovich Enukidze (1877-1937), a Georgian who, from 1922 to 1935, was chairman of the boards of the Bolshoi Theatre and the Moscow Art Theatre MKhAT and who was, like Steiger, also working for the Narkompros. Enukidze plays also a role in The Master and Margarita: he was the prototype of Arkady Appolonovich Sempleyarov, the self-satisfied chairman of the Acoustics Commission of the Moscow Theatres, who said in chapter 12 that «the mass of spectators demanded an explanation». As a result, Koroviev gave an unexpected explanation: he revealed that, the night before, Arkady Sempleyarov had visited the actress Militsa Andreevna Pokobatko, with whom he spent some four hours, while his wife believed that he was at a meeting of the Acoustic Commission.

Charles Thayer (1910-1969), an employee at the American Embassy in Moscow in Bulgakov's time, mentioned baron Steiger in his book Bears in the Caviar (1951):

«By 1937 the great Soviet purge trials were getting under way and the isolation of foreigners in Moscow was practically complete. One after another of my old friends either had disappeared or broken off all contact with us. It had never been easy to have friends among the Russians, and it hurt when the few who had been friendly with us began to turn their backs when they saw us in the streets or in the foyer of the Opera House. Every two or three days we read in the papers the name of some acquaintance who had been convicted of espionage or had confessed to sabotage or had been denounced as a traitor: Tukhachevski, Yegorov, Radek, Bukharin and the fabulous Baron Steiger.

Steiger came from an old Baltic family and at the time of the Revolution had thrown in his lot with the Soviets. Some people said that he did it to get permission for his father to emigrate to France. Whatever the reason he seemed to have served the Soviets weIl. He was a cultured man with an excellent sense of humour and a fund of stories which he loved to teIl in flawless French. He had some mysterious connections in the Kremlin and often served as a short cut between it and the foreign Embassies where he spent most of his time. Once after Stalin had told one of our Ambassadors how much he liked Edgeworth pipe tobacco, it was Steiger to whom I was told to deliver a tin of Edgeworth once a month.

As the tempo of the purges increased, Steiger seemed to grow more and more depressed. But he never failed to turn up at every diplomatic function. One evening after a cocktail party at the Embassy I was taking Steiger home in my car. The newspapers that day had announced that several of our mutual friends had been executed by the usual Soviet method - shot through the back of the head.

As we drove through the cold snowy streets Steiger was unusually silent. I tried to make conversation about the weather. «Yes,» he finally replied. «It is dangerous weather - very treacherous. In times like these one must be very careful to protect the back of one's head.» He stroked his neck and smiled. Then he lapsed into silence.

The very next day Steiger failed to turn up at an Embassy party. A few weeks later Pravda announced that Boris Sergeevich Steiger had been discovered to be a traitor and had been shot-through the back of the head.»

Charles Thayer, Bears in the Caviar, Michael Joseph Ltd., London, 1951, pp.155-156.

Other opinions

In 1933, in The Great Chancellor, an earlier version of The Master and Margarita, this character was called фон-Майзен or Von Meizen. According to Viktor Ivanovich Losev (°1939) [*], this is a reason for some scholars to assume that it was not Baron Steiger, but the literary critic Mikhail Gavrilovich Meisel (1899-1937) who might have been the prototype for Baron Meigel. Meisel regularly criticised Bulgakov in the early 1930s and had written, among other things, that Bulgakov had attempted to foist into print «an apology of the pure white guard» with his works.

In 1936, Meisel was arrested along with other writers from Leningrad and sentenced to 10 years in the Solovki prison camp. They were accused of participating in the so-called Trotsky-Zinoviev Center. This was a fictitious terrorist organisation made up by Josef Vissarionovich Stalin (1878-1953) to conduct the first major Show Trial in Moscow. Meisel did not stay in Solovki for long, though. In 1937 he was sentenced to death by an NKVD troika and executed.

It is, however, unlikely that Bulgakov would have thought of Mikhail Gavrilovich Meisel when he created Von Meizen's character in this earlier version of The Master and Margarita. After all, he described him as a бывший барон or former baron, which is clearly a reference to the status of Boris Sergeevich (von) Steiger.

[*] Viktor Ivanovich Losev is the compiler of My Poor Poor Master, a book that chronologically presents all surviving versions of The Master and Margarita.

Поместить эту страницу |

Московские персонажи

- Аннушка

- Арчибальд Арчибальдович

- Жорж Бенгальский

- Михаил Александрович Берлиоз

- Иван Николаевич Бездомный

- Никанор Иванович Босой

- Автор скетчей Хустов

- Латунский, Ариман и Лаврович

- Степан Богданович Лиходеев

- Савва Потапович Куролесов

- Профессор Кузьмин

- Барон Майгель

- Алоизий Могарыч

- Максимилиан Андреевич Поплавский

- Александр Рюхин

- Аркадий Аполлонович Семплеяров

- Андрей Фокич Соков

- Доктор Стравинский

- Тузбубен

- Писателей в Грибоедове

- Другие персонажи в Москве