Доктор Стравинский

Русский > Персонажи > Московские персонажи > Доктор Стравинский

Мы продолжаем напряженно работать, чтобы улучшить наш сайт и перевести его на другие языки. Русская версия этой страницы еще не совсем готова. Поэтому мы представляем здесь пока английскую версию. Мы благодарим вас за понимание.

Context

Doctor Stravinsky is about forty-five, as carefully shaven as an actor, with pleasant but quite piercing eyes and courteous manners. He's the director of the psychiatric hospital - «not a madhouse, but a clinic, where no one will keep you if it's not necessary» - in which some of the protagonists arrive for varoius reasons. The master and Ivan Nikolayevich Ponyryov, of course, but also Nikanor Ivanovich Bosoy, the «fat man with the purple physionomy, who was mumbling all the time about foreign currency in the ventilation». And in room 120 was brought someone who «was looking for his head the whole time».

When Ivan tells his story of Berlioz and their meeting with the devil, doctor Stravinsky's diagnosis is very clear and easy: «locomotor and speech excitation, delirious interpretations, complex case, it seems. Schizophrenia plus alcoholism, disturbed imagination and hallucinations».

In his discussion with Ivan he says it has no sense of keeping a healthy man in a clinic. So he would check him out immediately, if Ivan tells him that he's normal. Not prove, but merely tell. But then he manipulates the discussion in such way that, one given moment, Ivan's resistance breaks. His own will starts crumbling so to speak. He feels how weak he is and that he needs help… And he stays at the clinic.

Prototype

The Moscow psychiatrist, an adept of rationalism, has the same name as the imaginative composer Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (1882-1971), author of Sacre du printemps (The Rite of Spring) (1913), Petrushka (1911) and The Fire Bird (1910).

These three writings glorify wild instincts, elate pagan usages and the irrational, all things which doctor Stravinsky is professionally supposed to fight with. He is therefore subject, like Berlioz and Rimsky, to the influence of the musician of which he is the homonymous while he should be fighting his themes.

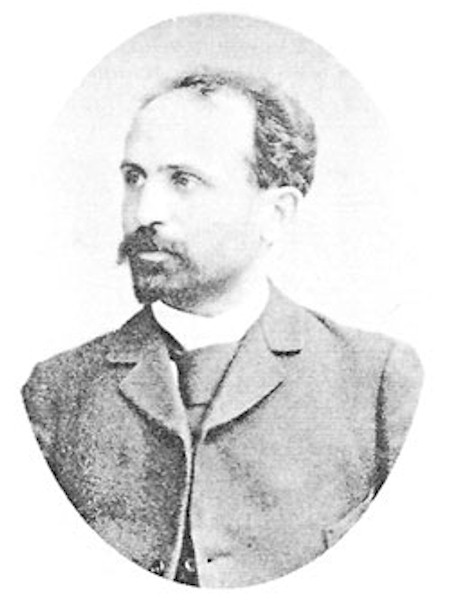

When Bulgakov started writing The Master and Margarita, Grigory Ivanovich Rossolimo (1860-1928) was the director of the hospital of the First Moscow State University - which is, by the way, also the place where bar tender Andrei Fokich Sokov would die of liver cancer. Grigory Rossolimo, who was the real life prototype for the character of doctor Stravinsky in The Master and Margarita, was in charge of the Laboratory for experimental psychology at the Neurological Institute. Just like the hospital where the master and Ivan arrived, the clinic of the First Moscow State University was used as a prison.

An hospitalisation as a mentally disturbed was a convenient method for the Stalin regime to eliminate «subversive» elements without ceremonies.

During the Great Purge, from 1934 to 1940, a mercyless witch hunt against former opposition leaders within the party, but also against heads of state, prime ministers and party leaders of the regional republics, intellectuals, artists, trotskists, right wing adepts and ordinary citizens was held. It was a well-proven method to manipulate people at interrogations in such way - with or without physical violence - that they had to become ill. Or that they at least admitted being ill.

After Stalin these practices were continued. The official psychiatric science in the Soviet Union had invented a specal definition for an «illness» called вялотекущая шизофрения [vyalotekushchaya shizofrenya] or slow progressive schizophrenia, which influenced just someone's social relations, without a trace of any other anomaly. According to a description given by the professors of the Центр социальной и судебной психиатрии им. В.П.Сербского or the Serbsky State Institute for Social and Forensic Psychiatry in Moscow there were, in most cases, ideas created about a struggle for truth and justice by «personalities with a paranoïd structure».

Some professors of this Serbsky Institute, like doctor Danil Romanovich Luntz (1912-1977), occupied high functions in the Ministry of Interior Affairs which administered some psikhushka's. A психушка [psikhushka] was a psychiatric institution with forced treatment. This treatment could be a restriction of the freedom of action, electrical shocks, a whole range of medications with long term side effects like narcotics, tranquilizers and insuline, and violence.

The poet, translator and dissident Viktor Aleksandrovich Nekipelov (1928-1989) also mentioned the unnecessary use of medical interventions like lumbar punctures.

Vladimir Bukovsky

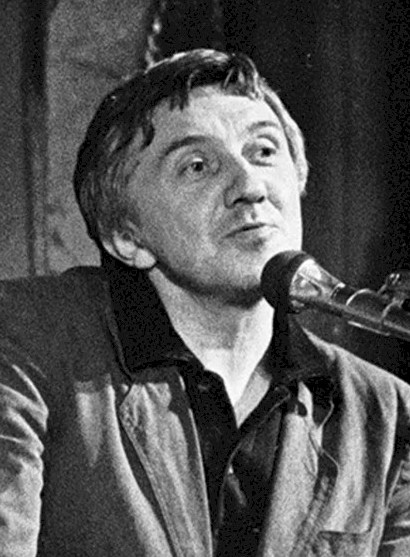

One of the first to out the use of psychiatric imprisonment as a measure against political prisoners in the Soviet Union was the dissident Vladimir Konstantinovich Bukovsky (°1942). He stayed for 12 years in prisons, labour camps and psikhushkas.

Bukovsky began to rebel at an early age. He was barely 17 years old when he was expelled from school in Moscow in 1959 for founding and managing an «unauthorized magazine». He had many clashes with the Soviet regime, and later with the regime of Vladimir Putin, but he is perhaps best known for his actions against psychiatric institutions in the Soviet period..

In 1970 Bukovsky had come into contact with Bill Cole, a correspondent of the American television channel CBS. Under the guise of a family trip with his wife and children and some friends, he went for a picnic in the woods outside Moscow. The KGB stayed in the background, watching them from a distance. Bukovsky was able to arrange things in such way that the officers could not see him while Bill Cole was filming an interview with him. In the interview, Bukovsky described how the Soviet government imprisoned political dissidents in mental institutions and subjected them to experimental treatments with various drugs.

Along with the interview, Bukovsky also managed to smuggle out more than 150 pages further documenting the political abuse of psychiatric institutions in the Soviet Union. The interview was smuggled out of the country by Canadian diplomats and broadcast by CBS under the title Voices from the Soviet Underground.

The interview and the information that Bukovsky had collected and sent to the West made human rights activists around the world and within the Soviet Union thinking. Bukovsky was arrested on March 29, 1971, and in January 1972 he was sentenced to two years in prison, five years in a labour camp and another five years in internal exile.

In December 1976, Bukovsky was deported from the Soviet Union to be exchanged at Zurich airport for Luis Corvalán, the Communist Party Secretariat General imprisoned in Chile. Bukovsky moved to the United Kingdom and settled in Cambridge, where he continued his biology studies which he had had to interrupt fifteen years earlier.

Anna Politkovskaya

According to the Russian journalist Anna Politkovskaya (1958-2006) the influence of the Serbsky Institute has not yet disappeared completely in today's Russia. In her book Putin's Russia she writes that, in 2002, professor Tamara Pavlova Pechernikova (1927-2007), who was heading the institute when Brezhnev was in power, and who worked there for 52 years, was called as a whitness-expert for the trial against Yuri Dimitrevich Budanov (1963-2011), a colonel of the Russian army who had raped and murdered the minor Elsa Visaevna Kungaeva (1982-2000) in Chechnya.

Despite the efforts of the - very old - professor to declare colonel Budanov iresponsible, the officer was sentenced by the court. «A very courageous decision», Politkovskaya said.

But she continues. In the Soviet era there existed the Kamera (Russian for «chamber») in Moscow, a nickname for the notorious KGB-laboratory no. 12, specialized in the preparation of different kinds of poison. When Boris Nikolaevich Yeltsin (1931-2007) came to power, it was closed down. But after a few years it opened again for «commercial» projects. «Russian businessmen who wanted to eliminate competition, made their orders at the laboratory. And when Putin came into power, the lab had a political customer again», Politkovskaya wrote.

Many Russian businessmen who wanted to eliminate their competitors placed their orders at the laboratory. «But when Putin came to power, there was also a political principal again», Anna Politkovskaya said. She knew what she was talking about, for Yuri Petrovich Shchekochikhin (1950-2003), her own deputy Editor-in-Chief was victim of a poisoning of which he died in 2003.

Click here to read more on Anna Politkovskaya and Yuri Shchekochikhin

Поместить эту страницу |

Московские персонажи

- Аннушка

- Арчибальд Арчибальдович

- Жорж Бенгальский

- Михаил Александрович Берлиоз

- Иван Николаевич Бездомный

- Никанор Иванович Босой

- Автор скетчей Хустов

- Латунский, Ариман и Лаврович

- Степан Богданович Лиходеев

- Савва Потапович Куролесов

- Профессор Кузьмин

- Барон Майгель

- Алоизий Могарыч

- Максимилиан Андреевич Поплавский

- Александр Рюхин

- Аркадий Аполлонович Семплеяров

- Андрей Фокич Соков

- Доктор Стравинский

- Тузбубен

- Писателей в Грибоедове

- Другие персонажи в Москве