The making of The Master and Margarita

English > Adaptations > Performing arts > Theatre > Mum Puppettheatre > The Making Of

Mum in Philadelphia was a puppet theatre: one that presents legitimate works of theatre with puppets. No kindergarten-like puppet shows here: even the family shows have a certain degree of artistry and craft that you wouldn't find at a kid's birthday party.

The Master and Margarita has hundreds of characters, making the work of Mum's puppet designer Martina Plag a little harder than for other pro-ductions. Although director Adrienne Mackey cut many characters from her adaptation, The Master and Margarita was still an overwhelming task for Mum Puppettheatre.

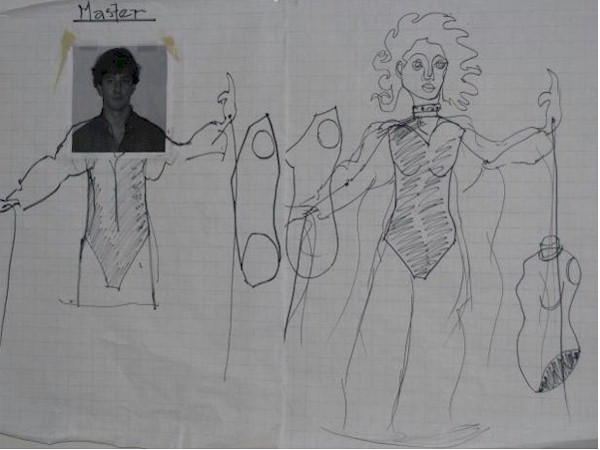

Plag, educated not as a puppetmaker but as an architect, approached the design and construction of her puppets as you'd expect someone with her background would. The designs were all drawn to scale in exact size, if possible, and typically, at least in the case of the human puppets, in normal human proportions, before initial construction could begin. Drawings had to be approved by the director of the play, and often, the actors were consulted to make sure that they would be comfortable with both the me-chanisms being used and the weight of the materials employed in the construction.

After designs were approved, the actors began rehearsing with dummy puppets - that is to say, puppets that could be maneuvered more or less like the final puppets with which they would be working - and Plag and her volunteers and interns could get down to work. They tried to get the puppets into the actors' hands as quickly as possible, however, because each handcrafted puppet moves differently.

For The Master and Margarita, the completion of some puppets was easier than others: the Satanic Woland's retinue was mostly composed of mo-dified toys, and the puppets in the toy theater were mounted one-dimensional drawings - but the human-like puppets had to be carefully and uniquely created by hand. The rod puppets in the Pilate scenes of the play were carved in wood and covered in leather, then carefully jointed so as to lend a degree of elegance to their movement. But the most complex puppets to create for the show were the tabletop puppets that appeared in the Moscow scenes of the play.

Although their foam bodies were essentially made in a one-size-fits-all kind of way, with adjustments made for body type and puppet size, each neoprene head was sculpted by hand in three layers. The layers were designed in profile: first one cheek, jaw, and eye socket, then the nose and chin, then the other cheek, jaw, and eye. After the layers were completed, they were fit together and their seams smoothed over until the head seemed to be one cohesive piece, and shaping was done to the face overall. Although psychology tells us that a perfectly symmetrical face is a sign of beauty, "that doesn't work onstage with puppets," says Plag. From the audience it's often hard to tell that the sides of the face don't match one another, but the effect works. "I make one side with angles and one side with curves. That way, if I turn him this way, the feeling is different than if I turn him that," Plag explained, demonstrating how the curved side of the face gave a gentler, more feminine feel to the puppet, and the angular side appeared more masculine and harsh. "People say all the time that they think they see their faces moving, maybe that they see the puppets wink." This, she continued, is probably because Mum rarely gave eyes to their puppets, opting instead for deep-set eyes under a heavy brow that simul-taneously dissipated the puppet's gaze and made it seem as if the puppet could actually focus on the people or puppets with whom he was speaking. "We suspend reality, but we also infuse a lot of reality into these puppets."

Details were then added to the puppets: if they were meant to resemble wood, for instance, as they are in The Master and Margarita, Plag applied a carving tool to the neoprene that made the rubber look grained and rough, as if it had been carved by hand. "People would have been making these by hand in Russia back then, with wood and a sharp knife," she said, explaining Mum's aesthetic choice for this production. Hands were made from polyurethane poured into rubber casts (traditionally, they're made from leather, clay, or wood - "Things that have been alive" - but this process saved a great deal of time and effort and was "easy for the volunteers to help with"), and then both hands and head were affixed to their foam bo-dies.

After the puppet construction was completed, there was nothing left to do but dress the puppets. Because, said Plag, "you can't really change a puppet's clothes," several variations of any character requiring costume changes were created, and the actors changed puppets accordingly, rather than having to redress them in the dark. All costumes were sewn on-site, specifically for the production.

Before the puppets were officially completed, they were given back to the actors for rehearsal. Both they and their directors took note of what worked and didn't work, often sending the puppets back downstairs for tweaks. "Sometimes, we're still building and changing through previews," Plag said. It's the price to pay for perfection.

Rehearsal

Some theatre companies

- Teater Accent - Stockholm

- Århus Teater - Århus

- Complicite - London

- Divadlo Pražské konzervatoře - Prague

- Fragments - London

- Lune de Mire - Lyon

- Mum Puppettheatre - Philadelphia

- Nemzeti színház - Budapest

- Oskaras Koršunovas Theater - Vilnius

- OUDS - Oxford

- Sharmanka Kinetic Theatre - Glasgow

- The Master Project - Los Angeles

- Theatre company Tryater - Leeuwarden

- Théâtre du Voyageur - Paris

Photos

The puppets' eyes are carved deeply

into their skulls so as to convey emotion.

The original designs drawn to scale.

The photo of Robert DaPonte is pasted

over the Master's head because the

puppet's face would later be crafted

to resemble him

Each layer is created individually, like a

slice of the head, and then the three

layers are put together

Robert DaPonte and Robert Smythe

rehearse with partially-complete puppets

Robert Smythe